Any reform of London’s Green Belt should be informed by economic assessment of the environmental value of Green Belt land.

A feature of land use policy in the vicinity of London is the designation of large areas as Green Belt, implying a prohibition on housing and other development except in very special circumstances. One reason why London’s housing is expensive is that demand is unconstrained except by price, while supply of a vital input – land with permission for development – is constrained by the Green Belt.

Two reports published earlier this year make a case for relaxation of Green Belt. London First’s report (3) focuses on Green Belt within the Greater London area, concluding that a small part should be released for housing development. It proposes that land be considered for release where it is close to transport nodes and of poor environmental value (4).

Two reports published earlier this year make a case for relaxation of Green Belt. London First’s report (3) focuses on Green Belt within the Greater London area, concluding that a small part should be released for housing development. It proposes that land be considered for release where it is close to transport nodes and of poor environmental value (4).

The Adam Smith Institute’s report (5) focuses more broadly on Green Belts across England, but is of great relevance to London. Its central recommendation is the abolition of Green Belt as a designation (6). This is less radical than it may seem, because much of the most environmentally valuable land within Green Belt is protected from development by other designations including Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Site of Special Scientific Interest. Having regard however to political practicability, it also suggests some alternative reforms, the most modest of which is the removal of Green Belt designation from all agricultural land within half a mile of a railway station (7). This is quite similar to the London First proposal, albeit it would apply to the whole of the Green Belt and not just the part within Greater London.

There is considerable overlap between the arguments of the two reports. Both point out that circumstances have changed since Green Belt was introduced in 1955. Population has increased. Higher incomes and wider car ownership have increased per capita demand for housing and associated off-street parking. Both emphasize the serious consequences of high housing costs, including high proportions of many people’s income spent on housing, people on low incomes living in cramped or inadequate accommodation, inter-generational inequity, and upward pressures on labour costs jeopardizing the competitiveness of internationally-traded goods and services.

My inclination is to agree that some relaxation of London’s Green Belt is appropriate. But there is something missing from both reports. Neither presents any figures comparing the economic values of land for housing development and undeveloped Green Belt land. Economic values here include not only market values but also non-market values of ecosystem services such as drainage, groundwater recharge, water purification, support for biodiversity, climate regulation, carbon sequestration and provision of green space for recreation. If, for some Green Belt land, its value for housing development exceeds its value as undeveloped land, even when all these non-market values of undeveloped land have been taken into account, then there is an economic case for relaxation of Green Belt. And that, surely, is the nub of the matter? On the one hand, environmental values must be included in estimating the net benefit or cost from housing development; on the other, those values must not be treated as infinite (which is the implication of saying that a site must never be developed, come what may), but must be properly estimated by the best available methods.

However, such a comparison of values is far from straightforward. Complications include the following:

- Different ecosystem services need different valuation techniques. Some require, in the first instance, an assessment of physical or ecological effects. How much groundwater is recharged from this land? How much carbon is sequestered by that piece of woodland?. The chain of effects must then be traced to a point at which a credible value can be assigned, such as the cost of providing water from the best alternative source, or a recognised carbon price. Others require revealed preference methods, eg valuing recreational green space on the basis of the travel costs incurred by visitors. Stated preference methods (asking people how much they would be prepared to pay for an environmental service), though controversial, may also be useful.

- Values will differ according to location and type of land use. The value of housing land tends to fall with distance from central London. The value of undeveloped land depends partly on location since some ecosystem services tend to be more valuable when provided close to where people live. The nature of the undeveloped land is also important: woodland, for example, has greater value for biodiversity and carbon sequestration than some other types of land use.

- The value of a piece of undeveloped land is not necessarily its value in its current use. Conversion from one type of undeveloped land to another – from arable farmland to grassland or woodland, perhaps – can increase its value, as has been shown in the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (8). In principle, therefore, value should be value in best undeveloped use, net of any costs of conversion or transition to that use.

- Ecosystem services associated with housing development also need to be considered. While blocks of flats surrounded by nothing but roads and paved areas may effectively be ‘environmental deserts’, most types of housing development in London provide some ecosystem services via gardens and local parks, which may indeed support more biodiversity than intensively cultivated farmland.

- The indirect effects of release of Green Belt land for housing development are also an important consideration. Will the development of a piece of former Green Belt land result, relative to what would have occurred if that development had not taken place, in a) more housing (overall in South East England), or b) a lower average density of housing within London, or c) less housing further from London, beyond the Green Belt, or d) some combination of these? What will be the effects on use of roads and railways, associated energy use and carbon emissions, and demand for new or improved transport links? These indirect effects need to be valued and included (added or deducted as appropriate) in the value of land for housing development).

- Values may need to be adjusted to correct distortions due to taxes, subsidies and restrictions on trade. For example, the market value of farmland may exceed its economic value because of the effects of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. Adjustments may also be needed in respect of price fluctuations due to economic cycles or asset price bubbles, so as to obtain values that are not distorted by temporary circumstances.

- More contentiously, a case can be made that values should be weighted on grounds of equity. If, for example, members of golf clubs are mostly well-off, a lower weighting should perhaps apply to the use values of golf courses. Carbon sequestration should arguably be given a higher weighting because it contributes to the mitigation of global climate change which poses a particular threat to people in poor countries.

- Allowance for future changes in circumstances is also important, conversion of land for housing being a decision with consequences for 100 years or more, and very difficult to reverse. What population changes can be expected, and how might these impact on land values? How might changes in transport systems and energy costs affect the trade-off many people have to make between housing and commuting costs? Will higher world food prices or insecurity of supply increase the value of agricultural land? Will the risk of North Sea storm surges, aggravated by climate change, eventually render some low-lying parts of London too risky for habitation? Such considerations suggest that the land values to be compared should reflect not just current benefits but expected streams of future benefits. They also point to a further element of value in undeveloped Green Belt land, namely, the option value implicit in retaining the opportunity for housing development at a later date.

- Finally (and this is perhaps the aspect that non-economists are most liable to overlook), it can be important to focus on marginal rather than total or average values. The amount of open access grassland and woodland within London’s Green Belt is very large. The total recreational use value of that land, reflecting (using the travel cost method) all the trips that people make to any part of it, is surely large. But the corresponding marginal value of a particular piece of that land, that is, the recreational use value that would be lost if that piece of land were no longer available for recreational use, may be very small, unless the site is of special importance, such as a famous beauty spot, or a difficult-to-bypass section of a much-used long-distance footpath. Most of those who would have visited or passed through that piece of land would probably visit instead a similar piece of land elsewhere, deriving similar enjoyment.

A comparison of land values which fully addresses all these complications (and others not mentioned) would be far from easy, and I am not aware of any published attempt to do so. The National Ecosystem Assessment is of considerable relevance in that it estimates values for many kinds of ecosystem services (9), but does not directly address the question of possible conversion of Green Belt for housing. An earlier study for the UK government by Eftec did plan to address this question by focusing specifically on the value of ‘urban fringe’ land, but was not completed (10).

The challenge is to find ways to cut through the complexity implicit in 1-9 above while obtaining results sufficiently robust to have credibility across all but the most extreme of the range of interested parties. The following are a few ideas:

a) It isn’t necessary to value all parts of London’s Green Belt. Obtaining credible values for a sample of areas of agricultural land within half a mile of a railway station would take the debate a long way forward.

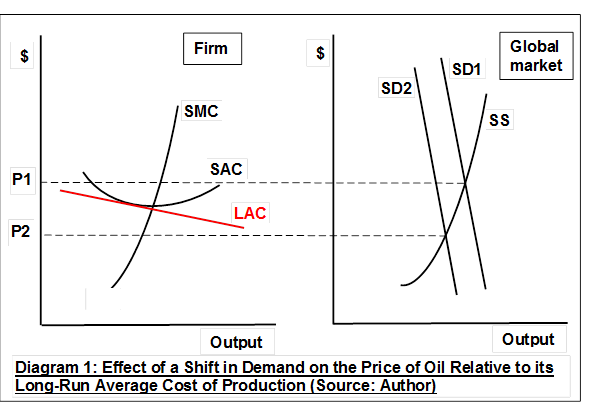

b) It may not be necessary to estimate environmental values very precisely. Suppose the value of a piece of land for housing development is estimated at £8 million per hectare (a plausible figure (11)), and its value in best undeveloped use at £100,000 per hectare. Then it won’t matter much if the latter is so inaccurate that it should have been £50,000 or £200,000: the conclusion would be clear in any case.

c) Values could be estimated on the basis of a set of assumptions which represents a worst case for housing development and a best case for preserving undeveloped land. Such assumptions might include a low scenario for London’s population growth, rising food prices and a rising carbon price. If, even on such unfavourable assumptions for housing development, the value of a piece of land for housing were found to exceed its undeveloped value, the case for releasing that land for development would be strong.

Notes and References

1. Wikipedia: Metropolitan Green Belt https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolitan_Green_Belt. 514,060 hectares, converted at 259 hectares per square mile. Also Wikipedia: Greater London https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greater_London [accessed 29/9/2015].

2. Papworth T (2015) The Green Noose: An Analysis of Proposals for Reform Adam Smith Institute (see map p 34) http://www.adamsmith.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/The-Green-Noose.pdf

3. London First / Quod / SERC (2015) The Green Belt: A Place for Londoners? http://londonfirst.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Green-Belt-Report-February-2015.pdf

4. As 3 above, pp 2 & 20.

5. As 2 above.

6. As 2 above, pp 5, 49 & 57.

7. As 2 above, 52.

8. Watson R & Albon S (Coordinating Lead Authors) (2011) UK National Ecosystem Assessment: Synthesis of the Key Findings p 43 http://uknea.unep-wcmc.org/Resources/tabid/82/Default.aspx A summary was also published in Bateman I et al (2013) Bringing Ecosystems into Economic Decision-Making: Land Use in the United Kingdom Science Vol 341 5 July 2013 pp 45-50 (see especially p 47).

9. Bateman I (Coordinating Lead Author) (2011) UK National Ecosystem Assessment: Chapter 22: Economic Values from Ecosystems Table 22.27 pp 1136-8 http://uknea.unep-wcmc.org/Resources/tabid/82/Default.aspx

10. Economics for the Environment Consultancy (Eftec) / Entec / MORI (2004) Valuing the External Benefits of Undeveloped Land Phase 2 Vol 1 (Draft for Office of the Deputy Prime Minister) [Accessed 29/92015 at http://www.eftec.co.uk/search-all-uknee-documents/search, entering keywords ‘External Benefits’] This report considers the design of a contingent valuation questionnaire, but Phase 3, implementation of the questionnaire, was not pursued (source: http://www.eftec.co.uk/eftec-projects/valuing-the-external-benefits-of-undeveloped-land-phase-2-designing-a-study).

11. Department for Communities & Local Government (February 2015) Land Value Estimates for Policy Appraisal https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/land-value-estimates-for-policy-appraisal. Within Table 1 pp 5-12,, see especially values per hectare for land with permission for development in the following London boroughs which contain significant areas of Green Belt farmland: Bromley £10,150,000; Havering £7,300,000; Hillingdon £11,600,000.